Watching Studio Ghibli’s first-ever all-CG anime was weird in weird ways【SoraReview】

These weren’t the bumps in the road I was expecting for Earwig and the Witch.

Earwig and the Witch starts off with a bold visual. We see a woman astride a motorcycle, her thick, curly red hair blowing in the wind as she moves down the highway. But what makes the scene especially striking for long-time anime fans isn’t the bike or its rider, but the car chasing them: a Citroën 2CV, which just so happens to be Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki’s car in real life.

It’s not the exact same model year as Miyazaki’s Citroën (the grille is slightly different), but the metaphor seems clear. The woman twists her wrist, opens up the throttle, and the bike surges ahead, leaving the Citroën (whose license plate starts with “MYZ”) behind as it sets its own course, just like Earwig’s embrace of CG animation is a departure from Ghibli’s traditional commitment to hand-drawn methods.

▼ Trailer for Earwig and the Witch’s upcoming English-dubbed version

Interest is sky-high whenever Ghibli announces a new project, but audience expectations for Earwig hadn’t reached quite the same altitude. For starters, Ghibli earned many fans’ love by, in effect, taking an anti-CG stance even as CG become the default format for animated feature films in the rest of the world. Japanese all-CG productions often don’t look particularly impressive either, and Earwig is directed by Goro Miyazaki, whose Tales from Earthsea is almost universally regarded as the weakest Ghibli film. Add in that Earwig is a made-for-TV anime movie (airing in a single uninterpreted block on Japanese public broadcaster NHK) instead of a mid-summer theatrical release, and a lot of people were keeping their expectations for Earwig in check…and now that it’s aired, it turns out that’s probably a good thing.

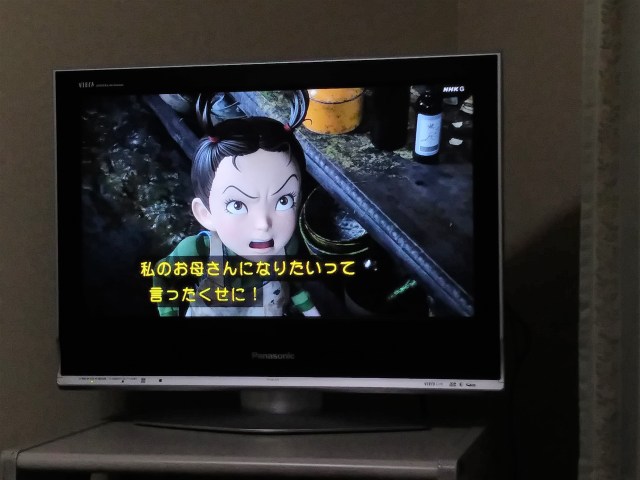

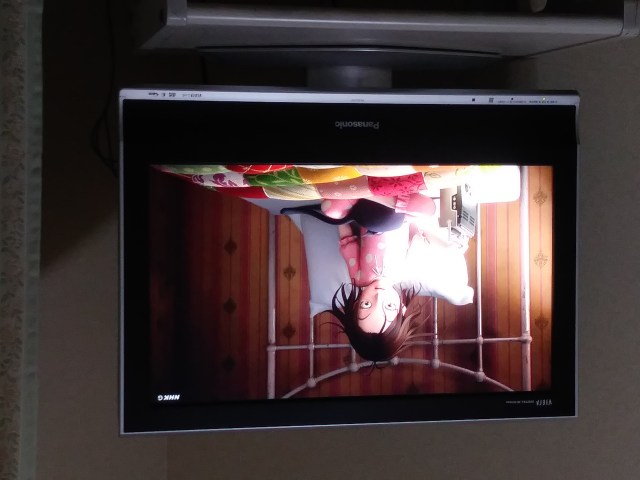

Let’s start with the visuals, which are actually one of Earwig’s strongest elements. Japanese all-CG productions don’t have the best reputation, often due to attempts to force-fit pseudo-hand-drawn elements into the characters’ movement. That’s not really an issue here, though. Earwig (renamed Aya for the Japanese-language version of the anime) moves smoothly and expressively, and her face displays a vast variety of different emotions with aplomb. The other characters are also capable physical actors, whether it’s potion-mixing witch Bella Yagga’s haughty heavyset struting, mysterious, possibly demonic Mandrake’s shoulders bunching up as he struggles to keep his ire in check, or the rest of the supporting cast emoting in their own ways. “Special effects,” so to speak, such as crackles of magical energy or a wriggling mass of earthworms, also move in a way evocative of Ghibli’s attention to dreamlike detail.

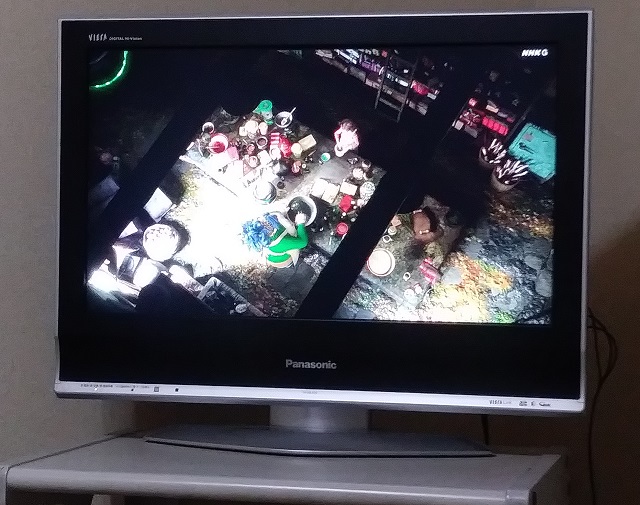

Earwig’s art team also proves to be impressively adept at rendering lush greenery, as the grassy grounds of Earwig’s orphanage and the jungle-like vegetation of Bella Yagga’s backyard both bring to mind prior Ghibli films in their abundance of color and care. Some interior environments lack the lived-in clutter and grit of their hand-drawn cousins (Bella Yagga’s kitchen, for example, doesn’t look as true-to-life as Whsper of the Heart’s Shizuku’s, for example), but it’s possible this isn’t because the CG team didn’t want to model knickknacks, and more to set up an extremely effective contrast for the first time Earwig sets foot in Bella Yagga’s potion workshop, which is covered in grime and overflowing with all sorts of cauldrons, alchemic flasks, and containers of magical ingredients, instilling the mixture of curiosity and trepidation that Ghibli heroines often find themselves feeling.

The production values are never as lavish as a CG theatrical release from Pixar or Disney, but pretty much from start to finish, Earwig looks good, with no distorted models or janky movement (though, sadly, the depictions of food are just OK, and not at the mouth-watering level fans have come to expect from Ghibli anime). The story, on the other hand, is where things get weird.

When we meet Earwig, she’s been left on the footstep of an orphanage as a baby, with only a cassette tape and a note from her mother, saying she’s on the run from “the 12 Witches” and that one day, perhaps years in the future, she’ll come back for her daughter. We then jump ahead 10 years to see Earwig as a happy free spirit who suddenly gets adopted by Bella Yagga. No sooner does Earwig set foot in her new home than Bella Yagga reveals that she’s a witch who only adopted Aya because she wanted an assistant, not a daughter.

From there, things settle into a pattern. Every day, Bella Yaga forces Earwig to work as her assistant, skinning snakes, harvesting herbs, and doing various other gross or menial tasks. Earwig starts each day with a plucky attitude, working hard in hopes that Bella Yaga will teach her to be a witch too, only for Bella Yaga to complain about how she’s not working fast enough, with Mandrake occasionally popping up to do something mysterious.

To Earwig’s credit, the dynamic is, at first anyway, interesting and enjoyable. Earwig neither crumbles under the burdens being placed upon her nor sacrifices her own well-being to try to please the obviously unpleasable Bella Yaga, and it’s refreshing how the story never treats her as helpless victim or selfless martyr. Both Mandrake and Bella Yaga are also eventually revealed to be more complex characters than they at first seem to be.

But while Earwig is taking its time setting up these relationships, the clock is ticking. At one hour and 22 minutes long, there’s really not much time to dawdle, but dawdle it does. We get a vague, half-explanation for the cassette tape that was left with Earwig as a baby, with the person giving the explanation explicitly saying they’re not going to explain anymore before shuffling Earwig out of the room. Earwig and Bella Yaga experience exactly one significant change to their relationship, and at the exact moment it seems like Earwig is ready to get to the meat of its story, the credits roll.

I’m not exaggerating with “exact” either. I watched Earwig as it aired with my wife, and when the credits started, she turned to me and said “I’m looking forward to finding out more in next week’s episode.” She literally thought this was an extended pilot for a TV series, and that’s honestly what it feels like, not in terms of visual quality, but in story and characters. There’re hardly any major plot developments to speak of. Did you want to know more about the 12 Witches? Looks like you’ll have to read the book, because the anime doesn’t tell you anything other than that they exist. And sure, Earwig is likable and the rest of the cast entertaining too, but the characters are static for almost the whole thing, with a just quick, confusing peek at who some of them used to be and a tiny hint at who they might become before we say goodbye to them forever.

Ghibli fans who came away disappointed with Tales from Earthsea and From Up on Poppy Hill might be quick to lay the blame entirely at Goro Miyazaki’s feet, but Hayao Miyazaki and fellow Ghibli co-founder Toshio Suzuki both served as producers on Earwig.

In the end, for as divisive as the decision to go all CG for Earwig was, the visuals really are the smoothest part of the ride (and the catchy soundtrack isn’t half-bad either). If nothing else, Earwig shows that, if it wants to, Ghibli can make a CG anime that looks good and still looks like Ghibli. Going back to the opening scene, Ghibli can, if it wants to, pull away from its past.

It just would have been nicer if Earwig had a more compelling place it was headed when it left the metaphorical Citroën behind.

Photos: SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Credit:

0 comments:

Post a Comment