English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect

But is there such a thing as too much confidence?

Something that’s not always clear until you actually try to do it is that communicating in a foreign language isn’t always a binary can-or-can’t situation. Sure, if you can’t speak a single word of whatever language you’re trying to converse in, the listener won’t understand you at all, but that doesn’t mean that anything less than perfect grammar and vocabulary will be completely unintelligible.

But again, until you build up some first-hand experience trying to talk to someone in a foreign language, it’s not uncommon to assume that if the words coming out of your mouth aren’t perfect, and thus not right, they must be totally wrong, and so no one will understand you. That can make the studying a new language intimidating and frustrating, and one Tokyo-based English conversation school has a clever advertisement that seeks to dispel that misconception and encourage Japanese people to give learning English a try.

めっちゃ納得した、英会話教室の広告。 pic.twitter.com/vB1weETpFf

— ことばと広告 (@kotobatoad) April 19, 2021

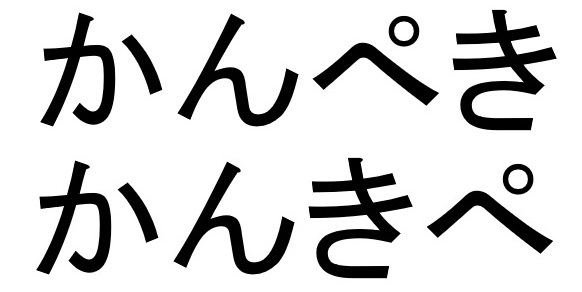

The Japanese text in the ad from Coper English, a copy of which was tweeted by @kotobatoad, starts with the statement “When you think about it, it’s not like we Japanese people always use perfect Japanese either”…and as proof, it purposely misspells the word for “perfect,” kampeki, as “kankipe,” which doesn’t actually mean anything.

▼ Top: “kampeki”

Bottom: “kankipe”

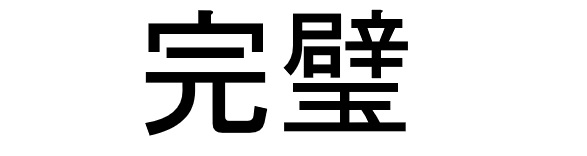

For that matter, writing kampeki as かんぺき, using the phonetic script called hiragana, isn’t the best choice either, since educated adults generally write it in kanji, like this:

It turns out that the ad’s message is peppered with errors. Tsukaettari / つかえったり (“use”) gets written instead as tsukkaetari / つっかえたり, juubun / じゅうぶん (“enough”) as jubuun / じゅぶうん, and on and on the mistakes go. And yet, Japanese Twitter commenters largely had no problem understanding what the ad is trying to say, which (after some fairly obvious corrections), works out to:

When you think about it, it’s not like we Japanese people always use perfect Japanese either. Sometimes we do, and sometimes we make mistakes or make typos.

But even still, like we’re doing here, we can somehow get our point across. We think that’s good enough when it comes to words and communication. So, please come learn English, with a lighthearted attitude. It’s OK even if you’re not perfect, because see, even these rough sentences can be understood.

It’s a warmhearted confidence booster, and @kotobatoad posted it while tweeting “This makes so much sense,” a sentiment many other Japanese commenters echoed with reactions like

“Exactly. Exactly. This is so inspiring.”

“So cool. It shows how important it is to try your best, and it’s bringing tears to my eyes.”

First and foremost, I want to say that in a lot of ways, I think it’s an extremely clever, and effective, ad. The assumption that you have to be perfect in order to be understood is a big reason many people don’t bother trying to study a foreign language in the first place, because they want to avoid embarrassing themselves and/or wasting their time should they fail to measure up to the standard of perfection. Instilling confidence in new learners, telling them “Come on, give it a try, you can do it!” and letting them know that their efforts will be rewarded even if they’re nowhere near fluent, are absolutely essential things schools and teachers need to do.

But there’s such a thing as being overconfident, as some of the other reactions to Coper English’s ad show.

“This makes perfect sense. I get the sense that I don’t have to bother studying English conversation in order to have people understand me.”

“It’s OK if your English isn’t perfect. If you just sort of line up English vocabulary words randomly, foreigners will understand you. You really don’t have to think that deeply about it.”

Yes, the idea that “Unless your language skills are perfect, they’re worthless” is a mistake. However, “It doesn’t matter how you use them, just toss out a bunch of English words and foreigners will understand you” is just as far from accurate.

▼ That sort of thinking can lead to things like the breakfast buffet in Japan that was serving something they called “near the broil with salt.”

Also, as clever as the ad is, the phenomena of being able to quickly make sense of garbled text and understand the intended meaning doesn’t translate directly into speaking and listening, the skills used in a conversation. For example, later in the thread someone posted this.

なるほど。これの日本語版ですね。 pic.twitter.com/RGFvPdtHiM

— Yuko(@yuko_in_dublin) April 19, 2021

If you’re a native English speaker, you probably didn’t have too much trouble figuring out what that text is trying to say. However, even though you’re reading from left to right, your eyes move and focus quickly enough that the amount of time between when you perceive the first letter and the last is negligible. For short, commonly used words, you’re basically reading the whole thing at once, not sounding it out phonetically in your head.

In a conversation, though, you can’t hear an entire word at once, and because a listener is receiving the information (sounds) in a more noticeably sequential manner, a listener can’t autocorrect as easily as a reader can. This is pretty easy to test by reading the above text (as-is) about the Cambridge University research out loud to someone, which is guaranteed to result in more instances of “Huh?” and “What?” than reading it in your head.

There’s also an inherent risk involved with relying on the person you’re talking to to essentially “fix” your words for you. They’ll naturally fix them in the way that aligns with their way of thinking, since that’s what makes sense to them. If you’re trying to say something different than what they would expect someone to say, though, you might end up with not only your intended message not reaching the listener, but with a different one, that you didn’t intend at all, being taken as what you really mean.

As a final point to consider, the kind of mistakes shown in the ad, and the Cambridge equivalent, are mostly jumbling up what would be the correct parts of a word, usually resulting in something that sounds similar but doesn’t actually mean anything, like with jubuun instead of juubun. That triggers a response of “Wait, that word doesn’t mean anything, but it sounds like another word that does.”

Those easy-to-notice-and-fix errors are far from the only kind of mistakes language learners make, though. Expressed in English terms, if you ask someone for “orgean juice,” they’ll probably still bring you a glass of orange juice. But if you’re playing so fast and loose with your vocabulary that you ask for “red juice” (“red” is pretty close to “orange,” right?) you might end up with tomato juice instead, and if all you can manage is “thingy juice,” you might not get anything to drink at all.

▼ If only I’d filled my canteen from the thingy pool at the last oasis…

But again, and I can’t stress this enough, the ad’s core message, “You don’t have to speak English perfectly in order to communicate, so give it a try!” is a beautiful and necessary one, and this is a clever way of delivering it. At the same time, speaking from several years of experience teaching English in Japan myself, I know there are sometimes Japanese students of English conversation who’d be much better communicators if they were more committed to making an effort to use correct grammar and vocabulary, instead of passing off the responsibility of decoding what they really want to say on the listener and making no effort to fix bad habits.

Ultimately, when speaking a foreign language there’s often a sizeable margin between “absolutely perfect” and “good enough to be understood,” and while passionate perfectionist linguists will probably always want to shoot for 100 percent, there’s nothing wrong with having a less ambitious goal. It’s important, though, for students to remember that even though they don’t need to be perfect, when trying to communicate, you’re not starting at 100 percent and slipping down the scale as you make mistakes. Before you open your mouth, you’re at 0 percent, and everything you can say correctly moves you up one tick closer to the “good enough to be understood” line. The most effective strategy isn’t being blasé about making mistakes. It’s focusing on maximizing your number of successes, congratulating yourself (plus getting ample encouragement from the teacher) for the things you do get right, and trusting that if you try your best, you’ll be able to get enough right that the person you’re talking to will understand you, even if your not prefect.

Source: Twitter/@kotobatoad via Hamster Sokuho

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert images: SoraNews24, Pakutaso, Wikipedia/Fiontain

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Credit:

0 comments:

Post a Comment