The twin joys and dual sadnesses of eating ramen in the U.S.

The food tasted great on our trip to this Seattle ramen restaurant, but some things were very different from what our reporter is used to in Japan.

On their overseas travels, P.K. Sanjun and the rest of our Japanese-language reporters like to do two things: immerse themselves in the local culture, and see what sort of inroads Japanese culture is making abroad. So when his stomach started rumbling on his recent trip to Seattle, P.K. asked one of his American friends if he could recommend a good ramen restaurant.

P.K. was in luck, as his friend quickly suggested Kizuki, a combination ramen restaurant and izakaya (Japanese-style pub). Overseas Japanese food can be sort of hit and miss, but Kizuki is managed by the same company that runs Kukai, a popular chain of ramen restaurants in Japan, so P.K. had high hopes for its flavor and authenticity.

Even though it was early in the evening on a weekday, almost every seat in the restaurant was full, and this was the first thing that made P.K. smile. It wasn’t all that long ago that Japanese food in general hadn’t yet achieved mainstream popularity overseas, and even after sushi earned favored-food status among the international foodie community, it was several years before ramen’s image in the west moved beyond cheap instant noodles. Seeing the people of Seattle experience the joy of restaurant ramen brought joy to P.K.’s heart as well.

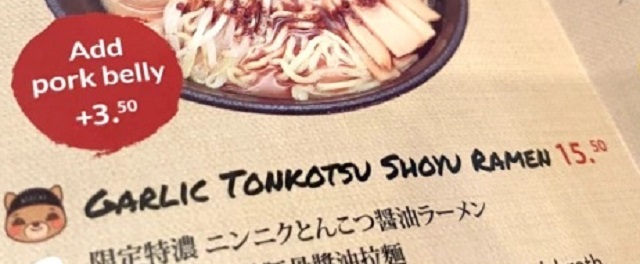

And the second thing that made P.K. happy? Kizuki’s ramen is legitimately tasty, and not by the more modest expectations P.K. has learned to apply to eating Japanese food outside Japan. Even judged by in-Japan standards for ramen, Kizuki does a great job, and P.K. thoroughly enjoyed the flavor of the garlic tonkotsu shoyu ramen he’d ordered, which the restaurant says is the most popular item on their menu.

However, there were also some things that P.K. wasn’t so thrilled about, starting with the price.

A bowl of garlic tonkotsu shoyu ramen costs US$15.50, which, at the time of P.K.’s trip, worked out to about 2,170 yen. That’s roughly twice the price of comparable ramen in Tokyo, and since that US$15.50 doesn’t include tax and tip, that bowl of ramen feels even more shockingly expensive. Granted, part of that is due to the yen/dollar exchange rate being pretty out of whack these days, but even at the more ordinary rate of somewhere between 100 and 110 yen to the dollar, you’d still be looking at the equivalent of somewhere around 2,000 yen after tax and tip, compared to around 1,000 yen for ramen in Japan.

But even more so than the price, the bigger shock for P.K. was the broth.

Like we said above, P.K. has no complaints in the flavor department. Kizuki’s broth, though, wasn’t hot. If you were feeling generous, you could maybe call it “warm,” but “lukewarm” would be the better description.

In Japan, ramen is served piping hot, but at Kizuki, the broth is cool enough that you can start chowing down the second the bowl is placed on your table. Looking around, P.K. didn’t even see anyone blowing on the noodles to cool them off, and when he mentioned to his friend how unlike Japan this is, his friend gave him the following explanation:

“It’s not just here. Pretty much all ramen restaurants in the U.S. serve their broth at this temperature. I think it’s because if the soup is too hot and someone gets scalded by it, they might sue the restaurant. It’s not such a big concern with things like pasta or pizza, but since ramen comes in a bowl, they’re probably worried about what’ll happen if it gets flipped over and hot broth spills out. So broth that’s this temperature is pretty much just an expected part of eating out for Americans, but for Japanese people like you, you’d probably like the broth to be hotter, right?”

Personal injury lawsuits aren’t unheard of in Japan, but they’re a lot less common than they are in the U.S. legal system. P.K. had never really thought about the traditional temperature of ramen broth being a safety hazard or legal liability.

Though his friend didn’t bring it up, it’s also worth noting that differences in table manners might be playing a role as well. In Japan, it’s permissible, and even encouraged, to audibly slurp your noodles, since it’s seen as a sign that you’re enjoying the meal. Slurping has a side benefit, though, in that it air cools the noodles as they gradually enter your mouth. On the other hand, American etiquette generally frowns on slurping, and if you’re inserting an entire mouthful of noodles directly into your mouth all at once, they need to be significantly cooler than if you were going to slurp them.

Whatever the reason, though, on this day P.K.’s ramen had come with a side order of culture shock. Not that he regrets his meal at all, though, and in fact he encourages everyone to give the ramen at Kizuki, or any other ramen restaurant trying to establish itself overseas, a try. Just be prepared that the experience might not be quite the same as eating ramen in Japan, even if the flavor is.

Related: Kizuki

Photos © SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Credit:

0 comments:

Post a Comment